Understanding the Role of Neuromuscular Dysfunction in the Pathophysiology of OSA

Written by: Dr. Luigi Taranto Montemurro, Chief Scientific Officer, Apnimed

Oct 13, 2025

Exploring the Interplay Between Muscle Activity and Neurotransmitters to Maintain Airway Patency, and OSA Implications

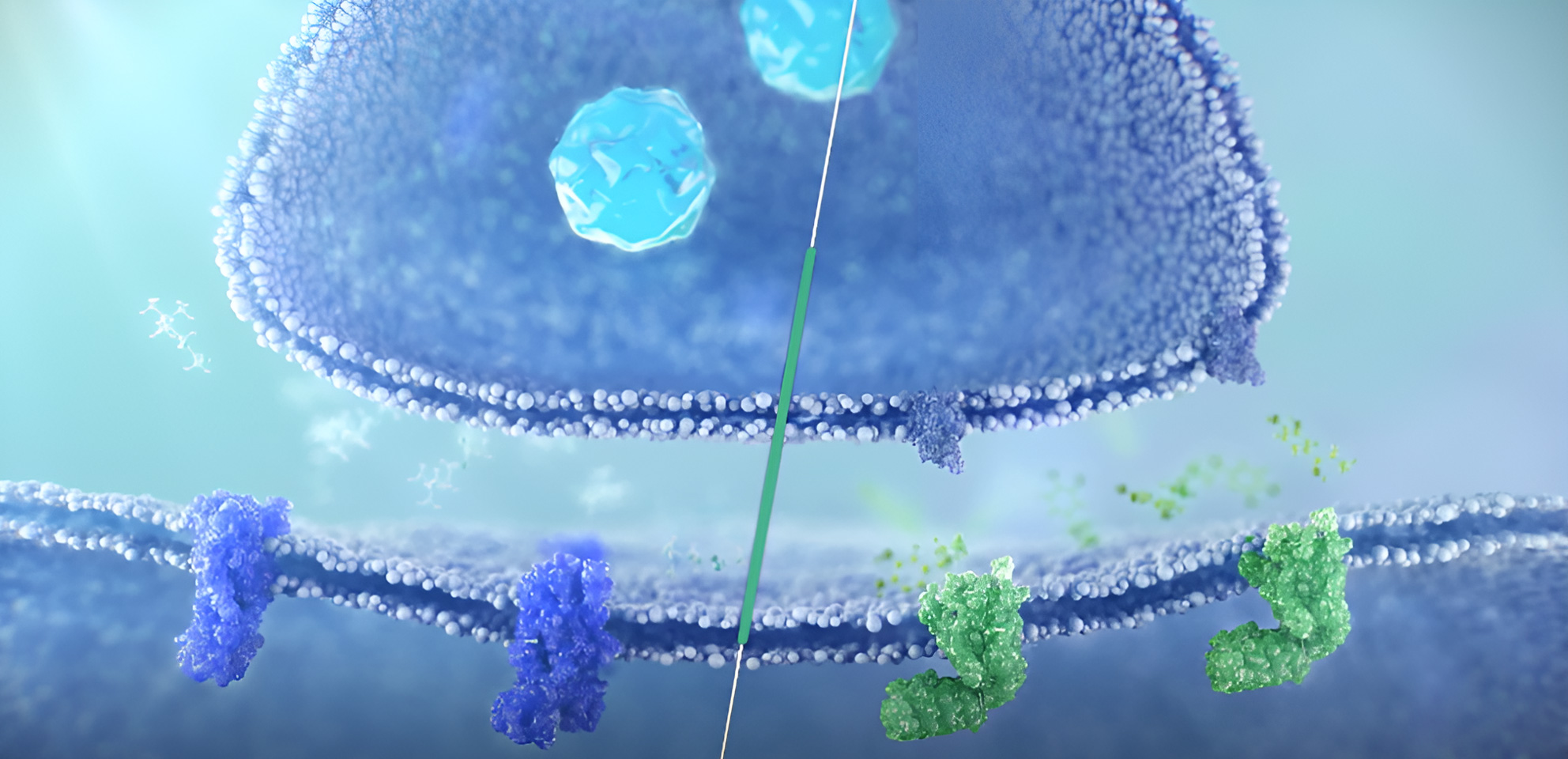

Breathing, though seemingly simple, is a remarkably complex process that involves the regulation and coordination of various muscles, including the upper airway (UA) muscles.1 Activation of these muscles to maintain airway patency is regulated by neurotransmitters, whose concentrations differ between sleep and wake states.2

Neuromuscular Regulation of UA Muscles

When a person is awake, neurotransmitters, including norepinephrine, innervate the hypoglossal motor nucleus which activates UA muscles to maintain their tone and keep the airway open.3,4 However, during sleep, the activity of these muscles decreases due to progressively lower norepinephrine input throughout the sleep stages.4,5 Additionally, muscarinic receptor-mediated inhibition of genioglossus activity during REM sleep further reduces upper airway muscle tone.6 This diminished neural input to key pharyngeal muscles (genioglossus, geniohyoid, tensor palatini, levator palatini) makes the airway more susceptible to collapse only during sleep. Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) exhibit a greater reduction in UA muscle activity when transitioning from wakefulness to sleep.2,7 This may reflect compensatory overactivation of these muscles during wakefulness to maintain airway patency and counteract anatomical disadvantages, such as obesity or craniofacial structural predispositions.8

During sleep, despite the reduced UA muscle tone, compensatory reflexes can be activated in response to negative pressure, increasing UA muscle activity and helping maintain airway patency. In patients with OSA, this reflex is often diminished or less effective, making it more difficult for them to recover from partial or complete upper airway obstruction compared with individuals without OSA.9,10

Pathophysiology of OSA

OSA is characterized by sleep-related neuromuscular dysfunction and predisposing anatomical abnormalities.2,7,10 This condition is state-dependent, due to reduced UA muscle tone caused by low neural activation and/or poor muscle responsiveness to UA obstruction during sleep.5,9 Myopathic changes may also contribute to dysfunction.4 These can be due to a variety of reasons such as mechanical trauma from vibration leading to local inflammation and remodeling of muscle fibers, neurogenic injury due to intermittent hypoxia and fat infiltration in UA muscles in obese people.11

Individuals without OSA, including those with predisposing anatomical abnormalities, can maintain airway patency even during sleep. This is largely due to the effectiveness of compensatory mechanisms, most notably the negative-pressure reflex, which enhances UA dilator muscle activity in response to collapsing forces, thereby stabilizing the pharyngeal airway and preventing obstruction. This underscores the essential role of neuromuscular dysfunction in the pathophysiology of OSA.9,12,13

Clinical Manifestations and Risk Factors

OSA is characterized by recurrent UA collapse during sleep, leading to chronic intermittent hypoxia, fragmented sleep, and significant systemic health consequences.2,4,14 Chronic intermittent hypoxia and reduced oxygenation are major contributors to extensive comorbidities including cardiometabolic disease, neurocognitive impairment, and early mortality associated with OSA.14 The narrowing of the UA is driven by both anatomical factors like obesity or enlarged tonsils, and low muscular response. Other anatomical risk factors include increased airway length, craniofacial structure, hyoid bone position, and tongue volume.1

Emerging Science and Innovation

Recent research, including therapeutic strategies such as hypoglossal nerve stimulation, highlights the critical role of neuromuscular dysfunction as a root cause to upper airway instability, challenging the traditional emphasis on obesity-related anatomical changes.15 The role of the neuromuscular function plays a fundamental role regardless of weight class, age, gender, or symptoms highlighting its fundamental role in the OSA pathophysiology.4

Recognizing neuromuscular dysfunction as a key driving force in OSA opens the door for novel treatment approaches beyond existing therapies like CPAP, which although millions use, an estimated 9-11.7M US adults refuse, discontinue or underuse.16 While there are limited management options designed to target neuromuscular dysfunction, this area is receiving increasing attention.17 Research into novel pharmacological methods of increasing UA muscle tone can provide additional, much needed treatment options for OSA management.

References

1. Dempsey J. Pathophysiology of Sleep Apnea (vol 90, pg 47, 2010). Physiol Rev. 2010;90(2):797-798.

2. Taranto-Montemurro, Messineo, Wellman. Targeting Endotypic Traits with Medications for the Pharmacological Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. A Review of the Current Literature. J Clin Med. 2019;8(11):1846. doi:10.3390/jcm8111846

3. Grace KP, Hughes SW, Horner RL. Identification of a Pharmacological Target for Genioglossus Reactivation throughout Sleep. Sleep. 2014;37(1):41-50. doi:10.5665/sleep.3304

4. Perger E, Taranto-Montemurro L. Upper airway muscles: influence on obstructive sleep apnoea pathophysiology and pharmacological and technical treatment options. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2021;27(6):505-513. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000818

5. Chan E, Steenland HW, Liu H, Horner RL. Endogenous Excitatory Drive Modulating Respiratory Muscle Activity across Sleep–Wake States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(11):1264-1273. doi:10.1164/rccm.200605-597OC

6. Grace KP, Hughes SW, Horner RL. Identification of the Mechanism Mediating Genioglossus Muscle Suppression in REM Sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(3):311-319. doi:10.1164/rccm.201209-1654OC

7. White DP, Younes MK. Obstructive sleep apnea. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(4):2541-2594. doi:10.1002/cphy.c110064

8. Mezzanotte WS, Tangel DJ, White DP. Waking genioglossal electromyogram in sleep apnea patients versus normal controls (a neuromuscular compensatory mechanism). Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1992;89(5):1571-1579. doi:10.1172/JCI115751

9. Fogel RB, Trinder J, White DP, et al. The effect of sleep onset on upper airway muscle activity in patients with sleep apnoea versus controls. J Physiol. 2005;564(2):549-562. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2005.083659

10. Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of Sleep Apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(1):47-112. doi:10.1152/PHYSREV.00043.2008

11. Kimoff RJ. Upper Airway Myopathy is Important in the Pathophysiology of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(6):567-569. doi:10.5664/jcsm.26964

12. McGinley BM, Schwartz AR, Schneider H, Kirkness JP, Smith PL, Patil SP. Upper airway neuromuscular compensation during sleep is defective in obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2008;105(1):197-205. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01214.2007

13. Cheng S, Brown EC, Hatt A, Butler JE, Gandevia SC, Bilston LE. Healthy humans with a narrow upper airway maintain patency during quiet breathing by dilating the airway during inspiration. J Physiol. 2014;592(21):4763-4774. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2014.279240

14. Dewan NA, Nieto FJ, Somers VK. Intermittent Hypoxemia and OSA. Chest. 2015;147(1):266-274. doi:10.1378/chest.14-0500

15. Strollo PJ, Soose RJ, Maurer JT, et al. Upper-Airway Stimulation for Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Survey of Anesthesiology. 2014;58(4):205-206. doi:10.1097/SA.0000000000000069

16. Watson N, Yu K, Campbell D, et al. 0637 Prevalence and Unmet Need of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in the United States . SLEEP. 2025;48(Supplement 1):A278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsaf090.0637

17. Taranto-Montemurro L, Patel SR, Strollo Jr. PJ, et al. Aroxybutynin and atomoxetine (AD109) for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: Rationale, design and baseline characteristics of the phase 3 clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2025;47. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2025.101538

Reviewed by: Apnimed Medical Affairs